Andrew Findlay

In Life After the Star Wars Expanded Universe, we take a look at science fiction and fantasy, why they’re great, and what they say about where our species has been and where it’s going.

Haruki Murakami has an awesome how-I-became-a-writer story. His parents expected him to snag a job with Mitsubishi and find a nice wife once he was secure. He married young and started a jazz bar, the Peter Cat. One: That is an awesome jazz bar name. Two: Something about saying “fuck stable employment, I’m going to open a jazz bar” seems like an especially risky thing to do in Japan. He continued running the bar until, at 29 years old, he saw a player hit a home run at a baseball game, and he suddenly knew he could write a novel. A lot of people say “I can write a novel!” to themselves. Not a lot then immediately go home and write an award-winning one, which is what Murakami did. At 65, he is one of the foremost practitioners of the post-modern novel of the weird. He usually builds the reality of his book out of the materials at hand, i.e the real world, but then takes those parts and subtly bends them until the world he bases on this one becomes haunting, unsettling, and strange. The proximity of the completely normal, unassuming world with the depths and strangenesses Murakami weaves through it creates a tension that is central to most of his work. In Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World, that dynamic is in full play, but he more explicitly includes science-fiction and fantasy in the mix.

I desperately want to travel back in time to the Peter Cat Jazz Bar.

Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World comprises two interwoven narratives, one science-fiction and one fantasy, that play out in alternating chapters. In the SF world, a data encryption specialist gets in way over his head. In the fantasy world, a newcomer with no memory of his self gives up his shadow in order to enter a strange town. The weaving itself is impressive – one of the signature Murakami pieces of weirdness is that these narratives are connected in a strange and unknown way that is very hazy at the beginning of the book. What is extraordinary is how perfectly Murakami hits the tone of each genre in the alternating chapters. In the SF chapters, Murakami creates a gritty, slightly grim world of loneliness and serious men doing serious things reminiscent of cyberpunk, and in the fantasy chapters, he perfectly captures the importance of place and the sense of timelessness that permeate a lot of the genre.

In the SF chapters (Hard-Boiled Wonderland), the narrative follows a man as he gets more and more involved in a dangerous conspiracy that he does not understand. The main science-fictional element of this world is that the main character is a Calcutec, an individual who has undergone brain surgery and training to transform his subconscious into a data-shuffling device. He takes a series of numbers, puts a pencil in his hand, goes into a trance, and then when he wakes up, he has run the data through his subconscious and shuffled it into a new, nearly-uncrackable code. Something about the uniqueness of each person’s consciousness and the chaos of the human mind make this the most secure form of data encryption – without the key, there is almost no way to decrypt the information. This is important, as the System, the giant data-protection agency which fields Calcutecs, is battling the Factory, an underground organization composed of Semiotecs whose main motivation is finding, decrypting, and selling top-secret information. The protagonist is hired by a mad scientist to protect his cutting-edge research. He does his normal thing, encrypts the data, but then people who desperately want that data make his life difficult. The main conflict in the Hard-Boiled chapters comes from the protagonist’s desire to stay safe and discover what is going on and why people are chasing him.

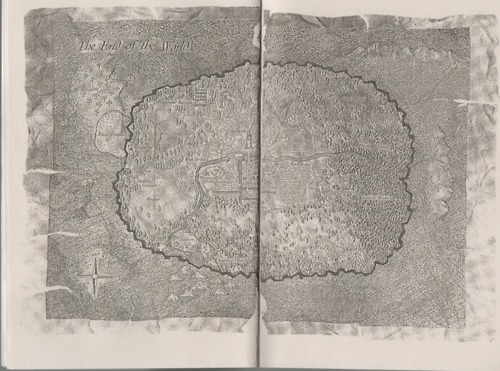

In the fantasy chapters, the narrative follows a newcomer around a mysterious town as he tries to figure out what is going on and reunite with his shadow. There are many magical elements to The End of the World, such as the protagonist having to give up his shadow, which becomes a separate, autonomous entity. There are unicorns that wander around the town during the day and are sent out the West gate at night. The central magic of these chapters, however, is dreamreading. The protagonist is assigned a job, as all inhabitants of the town are assigned a job. His is dreamreading, which consists of going to the library at night, going into the stacks, which contain shelves of unicorn skulls, taking them down, tracing the glowing lines on each skull with his fingers, and attempting to read the thoughts and dreams contained within. The point and method of this process is just as mysterious and unknown as the data encryption in the SF world, and each protagonist is just as confused and lost as the other. In addition to the magical aspect, another trait that makes these chapters a strong example of fantasy is Murakami’s attention to maps and places.

I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: It ain’t fantasy without a map.

The Town itself is a major character of the fantasy chapters, and one of the major differences between the two narratives is how much more important not just what is happening but where it’s happening is important to this one. The Town is a community which stands at the End of the World. It is surrounded by a gigantic, perfect wall, with only one exit: the West Gate, which is tended by the Gatekeeper. These locations are primal: There is only the Library, the Woods, the Pool, the Barracks, et cetera. Each location is just the capital-letter archetype of what it represents, and there are no clear place names. This adds to the haziness and nonspecificity of these chapters. All of the characters here are named for their occupation: the Librarian, the Colonel, and the Dreamreader, in addition to the Gatekeeper. A mildly sinister tone is set in the first chapter when the protagonist has to give up his shadow, and when the Gatekeeper starts seeming more like a warden than a keeper. The main conflict in The End of the World chapters comes from the main character’s desire to find out what the secret of the Town is and to reunite with his shadow.

The greatest success of this book is the flawless interweaving of each separate narrative into a cohesive, if jagged, whole, and Murakami’s masterful switching between tones and styles each chapter. To give an example of the perfect and nuanced difference in style, following are two excerpts from the book.

First paragraph of first SF chapter:

The elevator continued its impossibly slow ascent. Or at least I imagined it was ascent. There was not telling for sure: it was so slow that all sense of direction simply vanished. It could have been going down for all I knew, or maybe it wasn’t moving at all. But let’s just assume it was going up. Merely a guess. Maybe I’d gone up twelve stories, then down three. Maybe I’d circled the globe. How would I know?

First paragraph of first fantasy chapter:

With the approach of autumn, a layer of long golden fur grows over their bodies. Golden in the purest sense of the word, with not the least intrusion of another hue. Theirs is a gold that comes into this world as gold and exists in this world as gold. Poised between all heaven and earth, they stand steeped in gold.

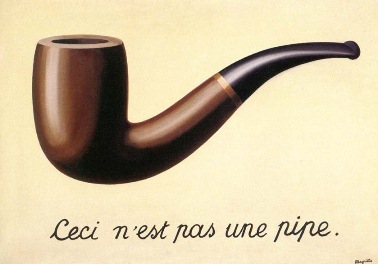

In the SF opening, the focus is on the thoughts of the narrator as he interacts with a piece of technology – an elevator. Rational, analytical thought dissecting all possibilities of movement and speed for the elevator he is riding to his job. In the fantasy opening, the focus is on rich, mythical description. The narrator describes the autumn coats of the unicorns, and they are not just gold and pretty; their coat color is a Platonic form of gold, “poised between all heaven and earth.” The focus is not so much on the analysis of the mundane as it is on the observation and experience of the mythical. This slight but powerful stylistic difference reverberates throughout each narrative, keeping them distinct even as the reader discovers how they are connected.

The main pleasure of this book comes from the dense accumulation of small, vivid details. The SF narrator spends a lot of time drinking whiskey, listening to jazz, and reading books. The fantasy narrator spends a lot of time going on long walks within the town walls. These sound boring, but Murakami’s descriptive power makes it pleasurable to read about the SF narrator eating a sandwich or the fantasy narrator walking to the Library looking at the sky. That is, Murakami’s talent makes his book interesting in parts that a lesser author would make unforgivably boring. Another strong point of this novel is its deep meditation on the nature of self. As the narratives cycle more and more tightly around each other, the major thematic focus of the novel shifts to questioning who each narrator actually is, what the significance of self is, and what identity means. The SF narrator becomes more and more preoccupied with who he is and what motivates him:

Once, when I was younger, I thought I could be someone else. I’d move to Casablanca, open a bar, and I’d meet Ingrid Bergman. Or more realistically – whether actually more realistic or not – I’d tune in on a better life, something more suited to my true self. Toward that end, I had to undergo training. I read The Greening of America, and I saw Easy Rider three times. But like a boat with a twisted rudder, I kept coming back to the same place. I wasn’t going anywhere. I was myself, waiting on the shore for me to return.

Everyone deals with constructing their own identity, trying to modify themselves either by strengthening their identity or trying to get away from it, and Murakami profoundly captures the futility and beauty of the struggle with that amazing line, “I was myself, waiting on the shore for me to return.” In addition to these discrete thoughts on self and identity, the narratives begin spiraling around each other in a way that structurally supports meditations on what existence is – I can’t really get into that part of it without hitting spoilers.

If you’ve been hearing buzz about Murakami for years but have not yet read anything of his, this is the place to start. It is not as long and sprawling as 1Q84, is more plot-driven than The Wind-up Bird Chronicle, and is a great book all on its own. The creation and sustainment of two distinct but intertwined worlds, the depth of detail he creates in each narrative, and the shattering profundity of the final reflection on what selfhood means all mark this as a book well worth your time.

Andrew Findlay has strong opinions about things (mostly literature) and will share them with you loudly and confidently. You can email him at afindlay.recess@gmail.com.