Andrew Findlay

In Life After the Star Wars Expanded Universe, we take a look at science fiction and fantasy, why they’re great, and what they say about where our species has been and where it’s going.

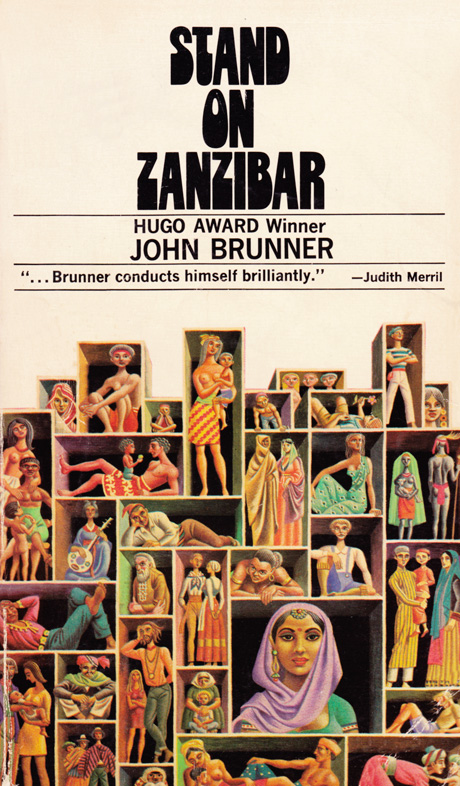

Isaac Asimov once predicted that by this time, many home appliances would run on atomic batteries. It would be so convenient: no need to use electricity and the battery would not run down within the consumer’s lifetime. Truly a marvel of modern science! In all seriousness, if Asimov’s failure to see anything wrong with a blender powered by nuclear fission does not clearly crown him as the king of all science nerddom, I don’t know what would. One of science fiction’s stocks-in-trade is predicting the future. Some suggestions are eerily accurate, and some are Jetsons-level laughable. Stand on Zanzibar is strange in that a weirdly high percentage of its predictions are absolutely correct.

The novel is set in 2010. The main pressure driving its plot is that there’s just too damn many of us. Brunner correctly placed the 2010 population of the world around seven billion, which is where the name comes from. Apparently, seven billion people, standing upright and shoulder-to-shoulder, would just barely fit on the island of Zanzibar. This foundational problem is not the only prediction Brunner gets right:

- “Muckers” go insane and go on senseless public rampages (Columbine, Aurora, Newtown)

- China is our main global competitor

- Europe has banded into a single political entity

- Detroit is a ghost town filled with abandoned warehouses

- Consumer culture is dominant

- News is highly processed and regurgitated on television in digestible bites

- There is legislation against tobacco but marijuana is legal

- Rent is so ridiculous in New York that a high-level executive has to have roommates to help him pay it.

Brunner misses a few things and gets a few other things wrong (in response to the population problem, there is eugenics legislation – people cannot have children unless they prove their genetic health), but the amount that he predicts correctly in this future is impressive. He gives texture and substance to his future world by using the Innis mode.

I found this while looking for Asimov quotations. Holy shit.

The book opens with a passage from Marshall McLuhan’s The Gutenberg Galaxy, which explains the Innis mode as constructing a mosaic of facts and events without perspective or unifying narrative. Brunner’s use of this mode strongly influences the structure of the book. There are four main types of “chapters.” Chapters labeled “continuity” follow the linear narrative of the story. “Tracking with closeups” present vignettes of characters not directly related to the main plot but part of the same world. “Context,” presents, you guessed it, context for the other parts of the story in the form of fake newspaper articles, works of sociology, and other types of analyses. Finally, “the happening world,” the most Innis-modian of these chapters, is a storm of assorted facts, sometimes as short as a single line, that assault the reader with the vibrance and freneticism of all the overwhelming information in the larger world outside the main narrative. The Innis mode generally and “the happening world” in particular serve to create an immensely dense world without sacrificing main narrative time to do it.

The main narrative consists of two parallel plots: U.S. intervention in an island nation in the Pacific, Yatakang, that is embarking on a “genetic optimisation program” to build a race of supermen, and a massive company called General Technics beginning a training program in a fictional West African nation in order to exploit mineral wealth off the coast. The Yatakangi storyline consists of a lot of great spy action and explosions. The U.S. intervenes because they either want to prove the genetic optimisation program is an impossible propaganda stunt or, if it is true, take steps to make it just an impossible propaganda stunt. One Yatakangi character tells the American spy that Americans just aren’t very good at letting other people be better than them at anything. The African storyline concerns Beninia, a country that is dirt poor, where education could be improved, and where starvation is a major concern. Beninia draws the interest of General Technics because, despite all of this, there has not been a murder there in the past 15 years, there is no open conflict or dissatisfaction, no vandalism, and no theft. In a world where people regularly run amok (the etymological basis for “mucker”) and kill as many people as they can before they are put down, the complete absence of murder indicates an inviting level of stability. GT agrees to put in place a 50-year program wherein they float the Beninians a huge loan, then use it to build all the most modern conveniences and supercharge their education so that, within those two decades, the Beninian population will be transformed into a nation of extremely skilled technicians and scientists with the knowledge set required to exploit the mineral deposits in the ocean nearby. This plan is created and vetted by the General Technics supercomputer, Shalmaneser. GT’s main claim to fame is this computer. It is next-level, near-A.I. type hardware, and its predictions are the main reason the company is so confident that their Beninia plan will work. They are in it for themselves, as they will be more than paid back by the wealth at the bottom of the sea, but they get to change the course of an entire nation for the better. The book tries very hard to sell the point that this is not neocolonialism pure and simple. The President of Beninia is complicit in the plan because he is dying and wants to leave a good future to his nation. Everyone involved in the project has their hearts in the right place and wants to help. Within the book, it is absolutely believable that this is a new and benign form of economic development. Outside of the book, this is basically a company owning a country outright, and in reality that never works out well for the owned. The disconnect between what happens in the book and the real-world probabilities make this conceit of the book ring a little hollow.

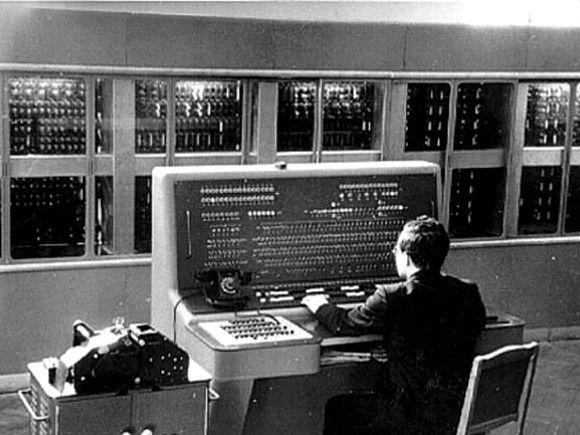

This is what Brunner means when he says “supercomputer.”

Speaking of things Brunner attempts that end up going wrong, he tries to extrapolate the future of race relations while sitting in front of a typewriter in 1968. He gets right that, due to anti-discrimination laws and the easing of overt racism, many positions of power are filled by African Americans, and racial tensions still simmer on. One of the main characters is a black vice president of General Technics. His roommate is white. They are both friends, but in their internal monologue, they each think really angry thoughts filled with racial slurs about each other. The problem is not that they get angry at each other, but that the sole source of a lot of their anger seems to be race. It seems outdated and strange, and indicates that Brunner, while trying to present a realistic future of race, was not fully free from many of his own preconceptions about it: In Brunner’s future, a relationship between equals of a different race seems not to be able to exist without some type of rancor. There is also no shortage of racist slurs against the Asian Yatakangi. Try as it might, this book is definitely a product of the sociocultural milieu of the 1960s.

Treatment of women in this book is just as big a problem as the treatment of race. There are no women involved as main characters, there are only two women in the entire book that have any real agency or power, and the current form of dating is something called the “shiggy circuit.” Codder is a mildly offensive term for a man, and shiggy is a mildly offensive term for a woman. Most young women participate in the “shiggy circuit,” a social construct in which women have no fixed abode and merely cycle around the city, moving in and out of the apartments of the men they sleep with, depending on them for food and shelter, and then moving on to the next one when either the woman or the man becomes bored. The easy interchangeability of women and the fact that they take up with the man and not vice versa necessarily places them at a disadvantage in relation to the men. This dynamic grows out of a problem that runs through many SF books written in the 50s and 60s. Most of the writers at that time were men, and many attempted to imagine new and more open sexual mores. The problem is that most of these new social systems ended up being not so much a representation of sexual progress as a result of the author’s subconscious thinking to itself, “Hey, wouldn’t it be cool if women were just naked? Like, all the time?” It comes off more as male fantasy than as balanced prediction (cf. Stranger in a Strange Land, The Gods Themselves).

Glad we’ve stopped oversexualizing women in science fiction. She’s a weapons specialist on the Enterprise, by the way.

Despite the jangling treatment of race and women, the book, in the form of Chad Mulligan, delivers wry, incisive, and apt criticism of society and the humans who run it. Mulligan is a pop sociologist and is the author of The Hipcrime Vocab and the amazingly-named You’re an Ignorant Idiot. He is deeply in love with the human race, which of course means he is intensely enraged by its stupidity. He becomes a main character by the end of the book, but for most of it we see snippets of his angry, incisive writings as excerpts in the “context” or “tracking with closeups” chapters. His main thesis is that if we don’t all change drastically we are all going to die, so act a little less insane and a little more rationally and lovingly. To give an idea of what kind of vision he has, I’ve included a handful of definitions from his Hipcrime Vocab.

The Hipcrime Vocab by Chad Mulligan:

(COINCIDENCE You weren’t paying attention to the other half of what was going on.)

(PATRIOTISM A great British writer once said that if he had to choose between betraying his country and betraying a friend he hoped he would have the decency to betray his country. Amen, brothers and sisters! Amen!)

(SHALMANESER That real cool piece of hardware up at the GT tower. They say he’s apt to evolve up to true consciousness one day. Also they say he’s as intelligent as a thousand of us put together, which isn’t really saying much, because when you put a thousand of us together look how stupidly we behave.)

Mulligan is a great character: contemptuous, competent, snarky, and broken-hearted by what he sees humanity doing to itself. He moves through the book spouting wisdom and being right about things, which isn’t necessarily a problem, but “irreverent middle-aged dude who is wiser than others” is a bit of an overused archetype in older SF.

This book has a lot to recommend it. It is a feat of worldbuilding, giving a nuanced and exhaustive picture of the world as it might exist in the future. Its narrative structure is innovative and effective. Its driving conflict is a problem that has affected, is affecting, and will affect the human race for the foreseeable future: increasing population, decreasing resources, and the tension and problems created by that dynamic. Its hope is that humanity finds a method to stop feeding on itself, but it presents the alternatives in horrifying depth and detail. It is a pity that, while many of the facts and events predicted are impressively accurate (the fall of Detroit, senseless acts of public slaughter, 24-hour news, the European Union), the conceptualization of race and women are mere extensions of the patterns extant in 1968. It represents a failure of imagination and a victory of narrow-mindedness in a novel otherwise exultant in its inventiveness, insight, and breadth. You still need to read this for what it does right.

Andrew Findlay has strong opinions about things (mostly literature) and will share them with you loudly and confidently. You can email him at afindlay.recess@gmail.com.

Image: LA Times