Andrew Findlay

In Life After the Star Wars Expanded Universe, we take a look at science fiction and fantasy, why they’re great, and what they say about where our species has been and where it’s going.

Editor’s note: an earlier version of this article mentioned that Philip K. Dick took a lot of LSD and wrote solely genre fiction. They’re both only partially true, and the article has been updated as a result.

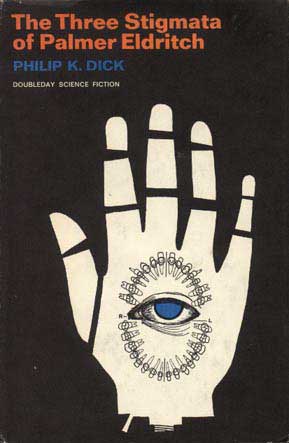

Philip K. Dick is the ultimate psychedelic writer. His explorations of the mutability of reality and the fragility of the human psyche are vivid, incisive, and hallucinogenic. Roberto Bolaño described him as “a kind of Kafka steeped in LSD and rage.” However much altered states influenced his writing, PKD did not actually do that much LSD – it gave him unpleasant experiences. Yup, he was just your run-of-the-mill, square, SoCal writer, ingesting massive quantities of amphetamines as he wrote feverishly, and as he wrote this book, he hadn’t even tried LSD for the first time. As I explain the concept of this book, it is very important to remember that Dick had not yet ingested lysergic acid. He was this crazy beforehand. I’m assuming every single novel PKD ever wrote deals with the nature of reality, its uncertainty and unknowability. I can definitely declare that each one I’ve read by him has always had someone losing their goddamn mind. In this 1965 novel, Dick explores the ramifications of self-medication when the medicine you use is powerful enough to make the universe drunk.

This book starts out in the far future, with many of the trappings of futuristic societies. Due to climate change, it is now too hot to be safely outside, and people have to wear special AC suits to prevent combusting while walking to work. The rich and powerful of the world vacation in Antarctica, which is nice and balmy. Most of the moons and planets of the solar system are colonized, but not happily. The UN runs the world, and in order to preserve humanity from the crumbling, condemned planet Earth, they instituted a draft for emigration. A certain percentage of Earthlings have to be induced to go to space colonies. They have to be induced because colonization sucks. On Mars, there’s nothing to do but tend your dying farm and hang out in your subterranean bunker. Well, that and taking powerful psychoactive drugs. Most of the action of the novel centers around the use of Can-D, a “translation” drug. Can-D is useless without Perky Pat Layouts, a company that makes miniature versions of all the stuff that can be found on Earth (this company also illicitly manufactures the drug). Think Polly Pocket, but extremely realistic.

Your new backyard, colonist!

It is so realistic because Can-D “translates” its users into the world of the layout. Therefore, if you take Can-D, some type of fungal hallucinogen, while sitting in front of a layout with a beach and a convertible, you get to spend a set amount of time living the life of either Pat, the woman, or Walt, her boyfriend, as they enjoy a seaside holiday. For some reason, the hallucination is dependent upon the layout – if you want to take a beach vacation, you better buy miniaturized beach towels and sun umbrellas. A feature that further complicates this already strange experience is that there are only two possible surrogates for the drug-user’s consciousness: either mini-Pat or mini-Walt. Women become Pat, and men become Walt. This means that if three male/female couples trip together in front of the same layout, all three women will be in Pat, and all three men will be in Walt, directing each as one member of a group conscious. Supremely weird, but honestly, if you were exiled to a barren sandscape where, if you’re lucky and terraforming is advanced enough, you might be able to go outside, wouldn’t you indulge in powerful psychotropics? Everyone in this book does, and that is the most plausible part of it – the human reaction to complete loss and mental stultification is to take stimulation wherever it can be found.

The conflict in the book starts when Palmer Eldritch, a kind of insane, spacefaring Richard Branson, returns from a ten-year voyage to Proxima Centauri with another fungus – Chew-Z. He begins marketing it immediately, and the Perky Pat people react with professional terror, because Chew-Z is a reality-altering drug that requires no layout, which means it is perfectly poised to put them out of business. Chew-Z is similar to Can-D in that it creates an alternate mode of existence for whoever takes it. However, it is much more powerful than Can-D. It can translate you into whichever existence you most want to be in – it is chewable wish-fulfillment. The problem is that, whatever new universe you make for yourself, Palmer Eldritch is there, and he exerts some type of control over your personal reality. If that sounds creepy, wait till you hear what his stigmata are: giant metal teeth, robotic eyes, and a metal arm. These are the three indicating marks you see on the people in your hallucination if Eldritch is taking control of them. Worst. Trip. Ever.

If I could hallucinate my very own universe, it would be the one in which the Nic Cage Superman movie happened.

A lot of the framework of this novel is pretty generic SF – spaceships that move fast and zip between planets, strange genetic therapies, and space colonization, but the social analysis and the ontological questions raised by drug use in this book make it interesting. First off, it is absolutely believable that the disaffected and depressed legions of press-ganged colonists would escape their bleak existence through whatever means necessary. The implications of their method of escape is also terrifying – if this creates a vivid surrogate reality, how do you tell when the high is over? Do you ever get out? Is this reality any less real than the one you experienced pre-dosing? Does it matter if it is or isn’t? These questions are hammered home again and again, and their lack of resolution strengthens the sense of loss and uncertainty and creepiness that permeate the book.

I love this man.

Philip K. Dick is fast carving out a very special place in my brain. I went on an expedition through his work after rewatching Blade Runner a couple of weeks ago. I have moved through three of his novels in the past couple of weeks, and each one is extraordinary. He went through a lot of his life very poor because, despite his prodigious output, he had trouble making money because critics relegated him to the genre fiction backwater. His catalog is overwhelmingly genre fiction, undoubtedly and unapologetically. What is important though is that this man always, always swung for the fences. It’s like he couldn’t help it. The characters might be lopsided, the plot might have pacing issues, and the setting might be overly lurid or unbalanced, but every one of his novels ends with you questioning existence, reality, and your conception of yourself. I have been a committed atheist for half my life, and one of his books had me (briefly) seriously considering the benefits of Gnostic Christianity. His writing is that powerful – while other books might explore what the problem is, his has you worrying over what “what” even signifies. I will take a sloppy book that asks what existence is any day over a perfectly-balanced artifact of a book that explores the problems of one neurotic family whose daddy didn’t give out enough love (I will never stop hating you, The Corrections).

Andrew Findlay has strong opinions about things (mostly literature) and will share them with you loudly and confidently. You can email him at afindlay.recess@gmail.com.

Images: Lit Reactor and IGN