Matt Matuszak and Brent Hopkins

In our new feature The Need to Achieve, two friends who don’t always see eye-to-eye evaluate a game they’ve both played just for the achievements. Beating 100% of a game can be both challenging and frustrating… How does One Finger Death Punch stack up?

First up on the list of games we have the dreams of attaining 100% in is One Finger Death Punch, an indie game that came out on Steam this year. The game was developed by Silver Dollar Games, which has a history of making low-budget games that tend to receive equally low-budget reviews. OFDP is the game that breaks the mold and has received rave reviews from media outlets because the concept is simple and pulled off intuitively.

Gameplay

Brent: C-

Matt: D (at best)

Brent: OFDP has you use the left and right mouse buttons to attack stick-men that converge on your character from the left or right side of the screen. One button press yields one punch, and through patterns you complete a variety of levels. This is akin to many rhythm games where memorization and rote muscle movement yield success.

The actual game itself is a bit of a mess. There are three difficulties, around six stage types, and over 100 stages to complete. You unlock special abilities (most of which are horribad) by beating stages. That means you will have to play this game a lot to get everything. This game gets old instantly and the stage variety is misleading, as half of them are filters added to obscure information and the other half are standard levels with either boss enemies or fast-moving weak enemies. This game is a grind and it loses its luster by the time you finish the tutorials.

Matt: OFDP starts off with five tutorial levels to explain that left click hits left and right click hits right. This should take 15 seconds to explain, but the developers must have thought they truly needed to teach everyone the difference between left and right. Once you get through the five tutorial levels, you get to just do the same thing 100+ more times because you’ve already done everything the game has to offer in those first five levels. You spend more time looking at where the enemy is coming from than watching the kung-fu moves your character is performing on the enemies.

Controls

Brent: A

Matt: A

Brent: Since everything is one-to-one, the controls are as good as the user. You can’t really ask for tighter controls than this.

Matt: I’m going to agree with Brent because left is left and right is right; it doesn’t get any more complex.

Sound/Music

Brent: F

Matt: F

Brent: The commentator in this game is horrible. He uses a fake Asian sensei accent and constantly babbles during the game. Worse yet, even if you turn off the sounds they immediately turn back on when the game starts up. The music was equally grating to me and I found that I instantly turned both off. The in-game sound effects (which you can’t turn off) are OK and help you keep up with the fighting on screen. The whole game is a bit too loud though, and I think Silver Dollar Games tried a bit too hard to make the game feel and sound like a old kung-fu movie and instead just made it sound grating.

Matt: This is the worst part of the game for me; there is no actual sound volume control. You have mute or not mute in the startup, but this data doesn’t save to your local machine so it always turns on when you start the game. The in-game sound effects are OK but the basic breaking or punching sound effects just play over and over again.

Story

Brent: F-

Matt: F

Brent: If there is a story I completely missed it for the last few hours I played this game. You are a stick man and you traverse levels, beat bosses, and learn kung-fu techniques. There is no development beyond that, though I suppose the game doesn’t require it.

Matt: There is no story in this game. You are a stick man that just has to fight the same things over and over again for no apparent reason.

Graphics

Brent: B+

Matt: C-

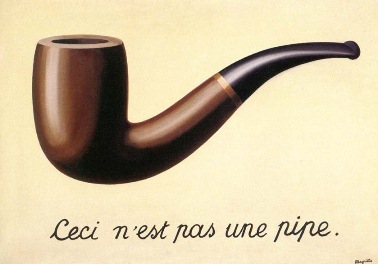

Brent: The game is very similar in style to the stick man fighting Flash videos made popular by Xiao Xiao in the early 2000s.

We know you all remember this.

This simplicity in design makes the game run smoothly and makes you feel like you’re playing as a stick man bad-ass. There are a variety of animations used, so it isn’t just jab left and jab right. The animations are smooth, though the way the game play works you don’t truly get to take in the action.

Matt: This is a very simple 2D game. There won’t ever be knockout graphics in a 2D game. However, they did a good job with the background imaging — which you will only notice if you can look up for longer than a second before another enemy comes from the left or right. The models for your character and enemies are both differently shaded stick figures.

Achievements

Brent: F

Matt: F

Brent: This is where the money is at. I chose this game without looking at the achievement list and that was a bit of a (huge) mistake. This game has 152 achievements and around half of them are easy to get on the lowest difficulty level. The other achievements are the ridiculous, as they ask you to kill THOUSANDS of enemies in a row on an endless mode with ever-increasing speed. Doing the normal levels with 200 enemies is crap, but trying to do 7000 is tiring to say the least.

Matt: I love out-of-reach achievements, so a game that has one extremely hard-to-get achievement I can appreciate. This game has 25 extremely hard-to-obtain achievements out of 152. 17% of the game’s achievements are near unobtainable unless you play a few hundred hours, and the gameplay isn’t worth a few hundred hours.

Overall

Brent: D

Matt: F

Brent: Too many achievements, repetitive gameplay, and sound that will make you pause and step outside are too much for me to recommend this game for hardcore gamers or achievement hunters. It’s a great casual game for some time-wasting, though.

Matt: Don’t buy this game! There are better games that meet the casual indie genre that have more story in the first five minutes of game than this entire game does. I dreaded having to play this game to write about it and am upset it lowered my average game completion percentage on my Steam profile.