Andrew Findlay

In Life After the Star Wars Expanded Universe, we take a look at science fiction and fantasy, why they’re great, and what they say about where our species has been and where it’s going.

French SF is relatively unknown in the United States. Discounting La planète des singes (Planet of the Apes) and Jules Verne, it has not carved out a strong presence in America. It might be that high-quality domestic product is glutting the market, as the only nation ever to put human beings anywhere other than Earth is also kind of a world leader in producing fiction about space and science. Most everyone who cares at all about books knows the names Isaac Asimov, Robert Heinlein, and Philip K. Dick. Let’s repeat that list with some big French SF authors: Jean-Marc Ligny, Xavier Mauméjean, and Pierre Bordage. If the final question at bar trivia had asked about anyone on that second list, would your team have been anywhere close to winning a free pitcher? I understand this imbalance to a certain extent. Having a strong French presence in the American SF market would make about as much sense as California merlot being the best-selling wine in Paris. The weird thing is, there’s almost no French presence in the market. Its profile is so minor that it’s the equivalent of people in Paris not knowing that California exists. It’s not because of lack of quality. La nuit des temps is among the best 1960s SF I’ve read. It’s certainly the best French SF I’ve read since Vingt-mille lieues sous les mers. Its quality derives from a combination of technical inventiveness, delightful early-SF pulpiness, and haunting social commentary.

America: being amazing since 1776

The opening paragraph of La nuit des temps (translated literally as The Night of Time, sold in Anglophone countries as The Ice People) signals a Big Problem from the get-go:

My beloved one, my abandoned one, my lost one, I left you there at the bottom of the world, I returned to my city apartment with its familiar furniture over which I’ve so often run my hands, the hands that love them, with its books that nourished me, with its old cherry bed where my childhood slept, and where, tonight, I sought in vain to sleep. All of this decor which witnessed me grow up, grow bigger, become me, today seemed to me strange and impossible. This world which is not yours has become a false world, in which I have never had a place.

Already, on page one, the narrator is reflecting upon the loss of his beloved. The reader knows from the start that this story does not end well, and this creates a tension that builds higher the closer the ending gets. The general background of the story is that, during the Cold War, a team of French scientists discover the ruins of an ancient civilization deep under the ice of Antarctica. When carbon dating places the ruins at 900,000 years old, hundreds of thousands of years older than human civilization, it incites international interest and passion. Pretty soon, an international team of scientists and a new research station are assembled at the location. They dig, and they find a buried city filled with wonders. Unfortunately, all of these wonders melt with the ice that held their molecules in place. All except one – the contents of a special Egg. Within the Egg, there is a strange generator and two human forms, male and female, encased in solid helium, preserved in a state of suspended animation at near absolute zero. The scientists decide to revive the female first. She wakes up, and the main narrative takes off. The main storyline is twofold. The first is concerned with international reaction to scientific developments at the station, the interrogation and assistance of Eléa, and the general tensions of the modern world. The second concerns the story of Eléa’s life in her ancient world, which the reader also knows will not end happily because her civilization has been annihilated.

The inventiveness of Bajarvel is a pleasure, and the book is filled with little pieces of technology either invented by the scientists or recovered from the ruins. One of the first that he introduces is the “eating machine,” which supplies Eléa with nourishment. It is a squat dome with buttons. She presses those buttons in a certain order, and the device produces colored spheres. These spheres are perfectly-balanced nutrition, and when the scientific team dismantles the device, they cannot find any raw materials. Eléa says the food is created from universal energy, the use of which her society had mastered through Zoran’s equation (the prospect of plucking limitless energy and materials out of thin air gets everyone on Earth’s attention). Unfortunately, Eléa is not a scientist and does not know the equation.

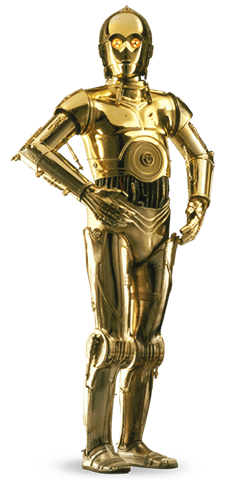

This is Zoran’s equation. Yea, the Antarctic scientists didn’t know either.

Another invention is the “serums” of her society, one of which increases the hardiness of the human organism, so much so that the word “fatigue” all but fell out of Eléa’s language. An experimental one that she took in order to survive the freezing process of suspended animation confers biological immortality. Biological immortality means that if you get hit by a truck, you still die, but you’ll never die from old age. Sadly, most futurists predict that, were humans biologically immortal, the average life expectancy would still be only about 200, because shit happens. Anyway, attractive tech. I love the next two examples of technology because they are so blatantly story-enabling. First off, there is a giant computer, the Translator, whose basic function is to provide translation between the many different languages of the international scientific team. Everyone wears an earbud connected to the computer, and the computer takes in whatever is said to the person, converts it to their language, and pipes it back into their ear. The blatantly story-enabling part of this machine is that they feed all the data they have on Eléa’s language into it, and after not really that long, her 900,000-year-old language is one the computer fully understands, enabling communication.

Did someone say implausible but plot-essential translation skills?

The other piece of tech that’s more narrative trickery than a machine is a brainwave reader. This is a device that, when put on the head, transmits thoughts. Its intended use is to pair it with another such device, thus allowing two people to communicate directly by thought. The scientists modify it so that it broadcasts to a television, meaning that, instead of Eléa having to talk about her life, she just puts on the circles, and up it pops on the Jumbotron. After they recover her, communicate with her, and turn the inside of her brain into quality TV programming, the narrative switches directly to describing what happens on the screen as the scientists watch. It explores the ancient civilization, which leads to a lot of the delightful pulpiness of the book.

First off, Eléa’s country is called Gondawa. It existed on Earth during a time when there was really only it and one other country, Enisor, on the same technological level with a few weaker nations scattered here and there (sound familiar?). The majority of their country was leveled by nuclear bombardment from Enisor, so they lived in extensive and beautiful underground cities, filled with plants and animals bioengineered to subterranean life. There are factories on the lowest levels of each city, factories which use Zoran’s equation to manufacture tools, structures, and implements from nothing. A central computer calculates the GDP of the country each year, and disburses an allowance equally to each citizen, to be used to purchase clothing, transport, and housing, and whatever other luxuries they might need. Very few people spend through their entire allowance, and it disappears at the end of every year to prevent the accrual of wealth. All of the machines and services are activated by a special ring worn by all citizens after their Designation ceremony. The Designation is a rite of passage from child to adult, at which citizens receive their numerical identification (Eléa’s is 3-19-07-91), their rings, and their partners. Yup, there is no dating in Gondawa. The central computer matches personality profiles of children to each other, finds ideal pairings, and designates them. This is probably the most utopian dream of the book, as the pairings result mostly in great happiness and sometimes in ineffable joy. Even bad matches are amiable and peaceful. Eléa had one of the second kind of matches, the perfect, soul-shatteringly intense level of love. The tragedy and pain Eléa feels from the second she regains consciousness is that as far as she knows, the love of her life, Paikan, has been dead for nine thousand centuries. The modern narrative circles around her inability to recover from this, and the ancient narrative circles on the development of her relationship with Paikan. The pulpiest parts of the book come from this relationship, which is high-octane, high-emotion, crowd-pleasing idealism. It is Romeo and Juliet, except the two people involved are not separated by a misunderstanding, but by the death of a civilization. The personal tragedy of two lovers is just one casualty of worldwide destruction, which forms the basis of this novel’s social commentary.

Their match.com profiles were 95% compatible!

There’s the standard advanced-civilization-versus-ours dynamic at play here, in which our society seems barbaric by comparison to the society of the visitor, but little things like Eléa not understanding why nudity is such a big deal (1960s male SF writer, folks) are not the main punch of the commentary. The frightening social commentary of La nuit des temps, doubly frightening when it was published at the height of the Cold War and when the collective insanity of Mutually Assured Destruction was in vogue, centers around the fact that an ancient humanity existed on a world with two superpowers and that there is now almost no trace left of that civilization. I will not get into specifics, but the Gondawans, in an attempt to avoid another war, built “l’Arme Solaire,” the Sun Weapon, as a deterrent. The function of the Sun Weapon is to concentrate the Sun’s rays on Enisor and basically melt the entire country. It backfired, both as a deterrent and as a weapon. The civilization that gave birth to it was wiped from the face of the Earth. Terrifying stuff to read, in 1968 especially.

You should give French SF a chance. Sure, if you search “Best French SF” on Google, the entire first page of results consists of the highest quality French restaurants in San Francisco, but you can always go to the French science fiction wikipedia page to look for good stuff. It is a vibrant and inventive branch of the genre. It produced La nuit des temps, which is a great novel filled with a heart-wrenching love story, fear-inducing social commentary, and a rewarding exploration of an extremely advanced society.

Andrew Findlay has strong opinions about things (mostly literature) and will share them with you loudly and confidently. You can email him at afindlay.recess@gmail.com.