In Major Issues, we look at one newly released comic book each week. Updated Fridays.

Gardner Mounce

Trees #3

Written by Warren Ellis

Art by Jason Howard

Published by Image Comics

Published: 7/24/14

As pop culture would have it, there are two ways that aliens are going to invade. There’s the Invasion of the Body Snatchers/Men in Black type where one day we find out that the aliens have been living right under our noses for years. And there’s the Independence Day/The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy type where the aliens just announce that they’re here and in a few seconds we’ll all be dead. The first thing we notice is that Will Smith has saved us from both types. The second thing we notice is that, in both scenarios, the aliens are accessible antagonists—they’re here among us for us to interact with or fight or whatever, or they’re above us in spaceships for us to throw rocks at. But imagine if an alien race left some undeniable symbol of their presence and utter superiority, and then just left us to scratch our heads about it.

In Warren Ellis and Jason Howard’s Trees, an alien race has punctured the globe with monumental, sky-scraping towers (which humanity has dubbed “trees”)—and then vanished, like, your move, humans, and haven’t returned or made contact for over a decade. Less us-versus-them-story and more human drama, Trees tracks a number of story lines that span the globe, from an ex-professor in Cefalu and the fascist’s girlfriend who stalks him to scientists in Antarctica studying a mysterious black bloom growing at the base of a “tree.”

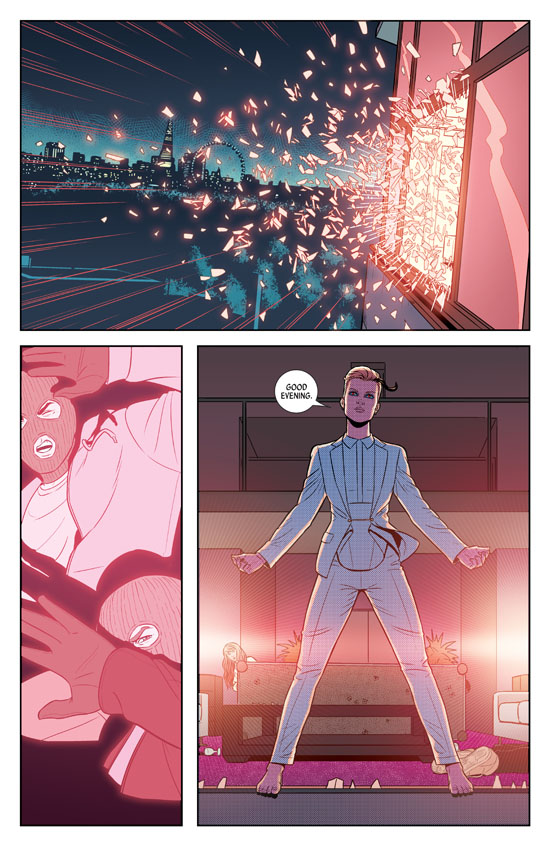

Ellis handles it all with incredible subtlety. A lesser writer would have written swathes of heavy-handed narration, but after some necessary exposition in the first issue Ellis constructs the world scene-by-scene with zero narration at all. A narrator-less story gives the sense that the reader knows just as much as the characters do about the trees—hardly anything. It also stresses the importance of the present moment: the world has halted since the trees arrived; they are ever-present, in nearly every scene; timeless and unchanging; dominating the landscape and laying waste to our sense of importance and human scale of time. Subtle also is Ellis’ dialogue. It’s been ten years since the trees arrived, so it’s only natural that people aren’t having exposition-heavy conversations about them. People are solving small problems on their own small stages, leaving the reader to synthesize bits of information to form the larger picture. The dialogue is smart, clipped, and avoids pandering.

Jason Howard is one of those imminently readable artists whose art is so functional that it’s almost invisible. It takes a keen eye to discern his moves. He uses the same types of panels over and over, and, taken together, the pages form a rhythm. There are the borderless panels that suggest timelessness, the bordered action panels that break the borderless panels up, and the white-backgrounded panels that strip the world down to action, reaction, and emotion. The borderless panels often establish expansive spaces like arctic vistas, sterile cafeterias, and “tree”-dotted Italian landscapes. These ground us in the sense of timelessness that the “trees” have imposed. These borderless panels are the arena on which the story takes place, and the places to which we always return: huge silent spaces punctuated by human action. Much rides on Howard’s colors, which he uses to establish mood. From cool conciliatory blues to altercation-accompanying yellows and pinks, his art is about subtlety.

Alien invasion stories are generally heavy on action and light on mystery. And we usually know the invaders’ intentions by the end of act one, which gives us plenty of time for preparing for fighting, fighting, and high-fiving over the fighting that just occurred. Trees stands apart because, first of all, there are no roles for Will Smith to play in the movie adaptation, and second of all, we don’t have any idea why the aliens dropped these “trees” down on us. To study us? To suck the life from our planet? To mess with us? The whole fun is that not knowing makes us feel out-of-the-loop and insignificant, and that fear of our insignificance spurs us. Fun, right?

Should You Get it?

Absolutely. As a writer, Ellis is confident as hell, and treats his readers with respect. These first three issues have been slim on action and heavy on establishing world, character, and conflict. He will not spoon feed, he will not pander. This is a serious comic for serious readers, and as with almost any Ellis comic, will most likely have tremendous payoff. Though, I will say, this comic might be more satisfying in trade paperback form where you can read a lot in one sitting.

Gardner Mounce is a writer, speaker, listener, husband, wife, truck driver, detective, liar. When asked to describe himself in three words, Gardner Mounce says: humble, humble, God-sent. You can find him at gardnermounce.tumblr.com or email him at gmounce611@gmail.com