Austin Duck

Typically, and, most likely, to your chagrin, I write about high-minded (read: pretentious) writing because, honestly, that’s what does it for me. I’m a bit of a douchebag, yes, (though who in English grad school isn’t?), but, more than that, I’ve spent so much time reading around, trying to find something that was intellectually and emotionally nourishing…

See, I stopped reading for fun or to be entertained a long time ago (I’ve never forget a lit. theory professor walking into our undergrad class and explaining “If you love to read, get the hell out of here. If you want to work, you’re where you belong” [she was a superbadass lady, obvs.]) and, instead, have grown to expect, even delight in reading a page and thinking to myself: What the fuck just happened? Where could this possibly be going? Why would the author say/do that, make that move, allude to that, etc.?

Sure, it gives me pleasure to think that I can keep up with, even anticipate, the moves of some of our most sophisticated artistic minds (again, because I’m a douchebag), but it also works to shape how I (and a lot of people I know) do other things: watch TV (just look at Jon May’s writing on this site), see movies, hell, sometimes (not always, but sometimes), it’ll affect how you read a restaurant menu. What I’m trying to say is that a pursuit like this, as needless (arguable) and pretentious (assuredly) as it may be, is powerfully altering.

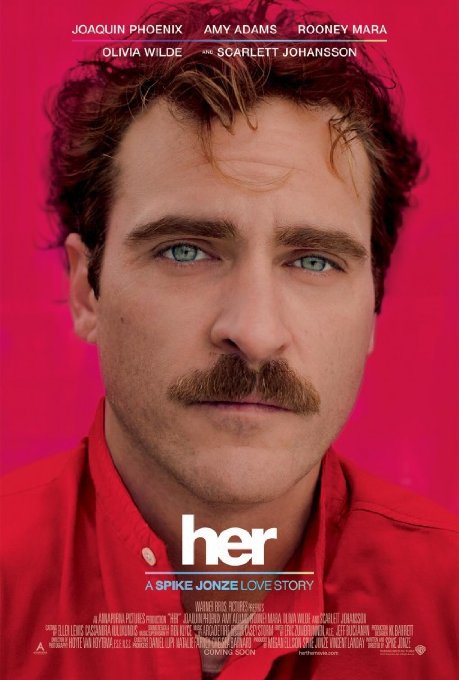

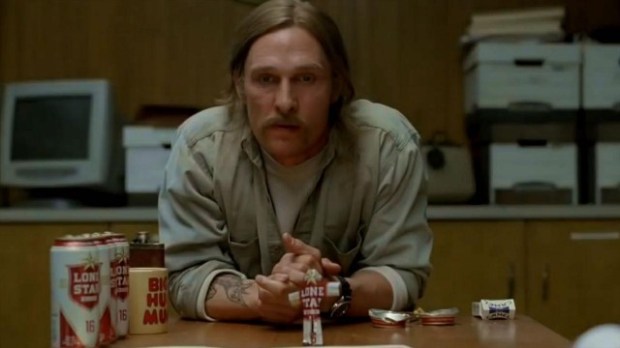

And that’s why I get so mad when something that could be outstanding — that, with all available evidence, should be outstanding — simply isn’t. I know a lot of you watch True Detective; you should; it’s completely excellent. I certainly won’t be trashing TD here because, various misguided (or not so) criticisms of gender, pacing, and over-dramatization aside, True Detective is an outstanding television show, and one that easily rivals (in its acting, its plot, its engagement with larger philosophical ideas) any Breaking Bad-esque show that keeps fanboys salivating and arguing its Shakespearean merits. Yes, it’s really that good. And what seems to make it so good is that the entire series (eight episodes) is directed by one person and written by one. There’s no room of writers kicking around ideas on this one; instead, it’s a developed, articulate, and extremely focused exploration of human depravity, corruption, and negativist philosophy.

So obviously, I was sold. I was like Nic Pizzolatto, where have you been all my life? Seriously. Noir and detective novels have always been something that I enjoyed, and, when I found out this guy started as a fiction writer and an academic, I was fucking stoked. Like the closet Homer Simpson that I am dutifully set aside my (now pretty serious) foray into contemporary Hungarian literature (I know, I’ll kill myself later), got some bourbon, and prepared myself for a good, old-fashioned page turner.

And then the problems started. Perhaps, though, my expectations just weren’t primed for the experience; I, after all, expected a sort of crime thriller, a novel similar in apparatus and execution to the show that’s put Pizzolatto on the map. Galveston (Scribner, 2011), however, is a completely different beast, a true noir centered around that a classic noir-trope: a search for a home that doesn’t exist, that was invented to give meaning to, and soothe the wounds of, the present.

It starts with seedy “bag-man” Roy Cady discovering he has lung cancer, learning that his girl has gone on to fuck his boss, and him being sent to do a “job” that he clearly isn’t meant to survive. However, of course, he does (as does the young prostitute Rocky) and the rest (or, at least, the majority thereof) is spent with these characters running from said boss, to Galveston specifically, to stay in the seediest ocean-front motel imaginable with a cast of characters that seem to be in constant competition to determine who’s the most revolting and outrageous.

So far, so good, right?

Wrong. Pizzolatto makes two fatal mistakes, ones that haunt the book through and through in their miscalculations. First (and foremost), what we know about Roy, the man we’re supposed to empathize with, to see ourselves in, to discover the nature of the American noir in: he’s dying, he has no problem killing people, and, sometimes, he’s willing to sacrifice himself for other people. That’s it. Obviously, this is a problem. The novel begins with this and, coupled with Roy’s fumblingly hard-boiled persona (one that works so well in classic noir fiction because, there, the impetus is plot over personal revelation), he never… really… grows. Sure, he’s a little bit of a softy, but we know that at the beginning when he takes Rocky along for the ride rather than leaving her for dead (and from his insistence that she’s too young for him, that he’ll never have sex with her). In fact, throughout, nothing about Roy, except the currency for which he kills (first for money, later for someone else’s well-being), changes dynamically.

As a result, Galveston seems to want to have it both ways: to show us Roy the hard-boiled bagman, the seedy, intentionally flat noir anti-hero who finds his way through a troubling and increasingly grotesque situation and to characterize, to develop, in Roy and Rocky, a wandering loneliness, a longing for things to go back to a way that they never were. Unfortunately, here, these points don’t converge.

Roy is always a bit aloof (though we follow him for the entirety of the novel), a little too-constructed by the traditional demands of the noir- and detective-genres, a little too flat, for his despair to be real. He’s just a variation on a cliché: a hitman with a heart of gold, a man who, in seeing his coming death, decides to help others. It all seems a little too easy. Instead, we’re left with a book that, though it is a page-turner and will quickly pass a lonely evening, doesn’t understand the story it wants to tell, doesn’t want to commit to the tragedy of being a piece of human garbage with a conscience (as we see in True Detective’s Rust Cohle), or to the remove and plot-focus of a dime-store mystery novel. Instead, it wants to walk a line between the two, a plot-driven noir with a bit of humanistic MFA-fiction learning (developing characters, creating emotional/philosophical centers that revolve around memory and trying to get back what’s lost) and, unfortunately, Pizzolatto doesn’t quite pull it off. The characters just simply aren’t present enough to join the two threads. And maybe that’s where True Detective succeeds; actors (especially really good ones) do have a way of injecting a little humanity.

Austin Duck lives and blogs in DC. He can be reached at jaustinduck@gmail.com.

Image source: EW