Alex Russell

Over the course of 2014, I watched every single movie that won the Oscar for Best Picture, from Wings to 12 Years a Slave. I started from the hypothesis that none of them could possibly be worse than Crash. When I first made that statement I’d only seen a handful of them, but my disdain for Crash was strong and my desire to test my theory was even stronger. I could only safely call Crash the worst of them all if I’d seen every single one.

There are 86 of them, and they total 11,866 minutes, combined. That’s a little under 198 hours, or roughly 8 and 1/4 days. I did not consider how big of a task just watching them would be, much less writing about them. That said, it was a fun journey. It took me an entire year. I’ve now done the research and I’ve got all the data I need to say this:

Crash is the worst Best Picture winner of all time. Period.

They aren’t all bad, though! Just because Crash is a hopeless look at a forsaken world through the eyes of stiff, unlikable robot characters is no reason to not run down the list and see what’s worth your time. I started this year saying that I wouldn’t do that thing where I ended this with a list, but lists are fun and I spent more than eight days watching these damn movies. Now, you get a list. We’re going in order of worst-to-best, and I tried to hold my criteria here to just the abstract of “best.” That said, this list is only my list, so it’s a good thing I’m also right about everything. When you watch all 86, you get to make a list. Disagree in the comments.

Thanks for reading all year! If you missed any (or all of ’em) you can click the links to read each individual writeup. Spoilers are very rare and only used when there’s no other way to talk about the film, but you’ll enjoy each more if you’ve already seen the subject matter.

(You may also want to check out Buzzfeed’s version. It isn’t my favorite site, but their list was invaluable in deciding when to watch a “good” or a “bad” one, and it’s a much more critical look at the list.)

“At one point, a character shoots a kid. The kid doesn’t die (because the gun is filled with blanks) and then the family walks away and leaves the shooter standing in broad daylight. If you shoot at my kid, we’re at least going to have a conversation.”

“Cimarron is an unmitigated disaster of a film. It’s slow, it’s weird, it’s boring, and it’s dated. There is absolutely no reason to watch Cimarron in 2014 aside from a desire to watch every Best Picture winner. This movie isn’t even fun to hate.”

“There is no larger narrative beyond “go around the world.” David Niven bets a bunch of stuffy British people that he can go around the world in 80 days. There you go. You can skip it now.”

“There was a campaign around the release of the movie to nominate the dog for Best Supporting Actor. I love dogs. In the spirit of a piece where I compare pieces of cinema, this would mean equating Robert De Niro with a dog.”

“Race is challenging, and a lot of people refer to movies like this as “Oscar bait” because they try to tackle the topic. They may be right, but winning the Oscar and being remembered fondly are different accomplishments. Dances with Wolves is just too hamfisted.”

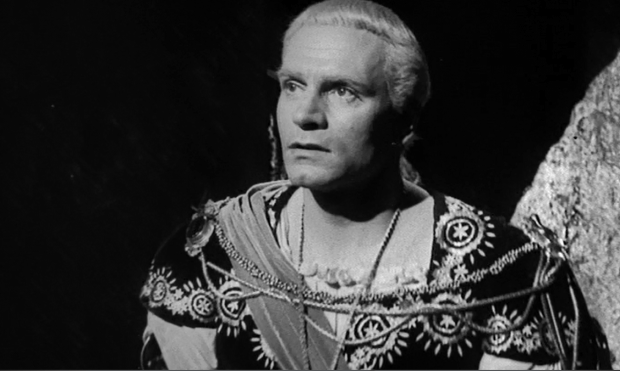

“Hamlet is not the story of a man who wants to have sex with his mother and can’t decide if he should kill his stepfather, or at the very least it is not that in that order, but if it has to be that to Olivier he has certainly succeeded in making what he wanted to make.”

“There’s really no draw here. It’s deeply, deeply boring, maybe beyond the abilities of anything else on the list. It would feel long at half the length, and there’s nothing to really sink your teeth into.”

“Lines are stepped all over, characters are never established, and huge diversions from the plot are common. That last one is the strangest trend about early Hollywood: everything made the final cut, no matter if it mattered for characterization, or the plot, or neither.”

“Gladiator may be the only Best Picture winner that has absolutely nothing to say. There are worse movies, to be sure, but there aren’t any that attempt to do less.”

“It’s real, real dated, y’all. The sexual politics of the love triangle (and fourth member, who gets added late in the film) will anger modern viewers, and there just isn’t all that much going on outside of that.”

“The journey isn’t “mean racist lady” to “nice old lady,” it’s “mean old lady who hates Morgan Freeman” to “somewhat less mean old lady who loves Morgan Freeman.”

“There are two kinds of “bad” Oscar winners: there are the Around the World in 80 Days kinds that are genuinely bad and win inexplicably and there are the Driving Miss Daisy and Gladiator kinds that seem fine at the time and almost immediately crumble upon future examination. Braveheartis that second kind. You see it on a list of Best Picture winners and just say, “Really? Okay.””

“The problem here is that no one ever asked the question “is 90 minutes of circus footage too much?” It really, really is, but in a world that includes some truly awful movies with Best Picture on their DVD box, you shouldn’t hate The Greatest Show on Earth. You just shouldn’t watch it, either.”

“This is old Hollywood at its old-Hollywood-est. It’s a crazy story that likely works well as a play but doesn’t make a ton of sense as a film.”

“How Green Was My Valley isn’t bad, but it’s a relic. It doesn’t really make sense anymore. It fills you with sadness for a people you can’t help. For an economy that has already bottomed out. In America we bemoan the death of our industrial cities, but How Green Was My Valley will put it in perspective: it has been thus for a long damn time.”

“It’s a really full movie — I would like to go into his wives and opium and pregnancy, but that part of the movie drags a bit — and it can be tough to watch as a result. The payoff is good, but the movie could have benefited by being more judicious with the editing.”

“The family argues with the IRS over income tax, which is fine. Then they… make unlicensed fireworks and set them off all over their house in the middle of the city. Okay, cool, 1938. Whatever you say. I guess that’s a thing now. Then, a man in a silly mask runs up from the basement to scare the police so they can go back to their xylophone song.”

“The joke consistently is that Tom Jones is in love, but he’ll just sleep with this woman in this patch of tall grass anyway. Comedy is in doing something so many times that it’s funny, then not funny, then hilarious, but I was pretty damn tired of Tom Jones the guy and Tom Jones the movie by the end of it.”

“There is absolutely nothing in Shakespeare and Love that is challenging or interesting. It’s just a series of events, well told and well acted, but not one that really engages.”

““Risky” is as nice of a word as I can use to describe the ending. I hate this ending. I hate, hate, hate it. It’s not spoiling it to say it ends with a “daydream” sequence that plays out as a ballet. I know it’s iconic and it’s exceptional and dazzling and all that, but it’s exactly what people think of when they say they “hate musicals.””

“The setup of the story of Sir Thomas More’s undoing is an interesting part of English history, but it’s not a very fascinating thing to watch. This thing wakes up like it doesn’t want to go to school in the morning. It’s almost 40% of the way into the movie before anything “happens” in a sense.”

“The entire movie is “climax” but my least favorite dramatic scene is a flower competition, and I would write more about it, but it’s a flower competition.”

“The ideas of a religion wanting to appeal to a new generation and the old generation being afraid to try new tactics still resonates all these decades later. The theme of giving way to your future is still universal, but the way it happens in Going My Way feels a little dumb towards the end.”

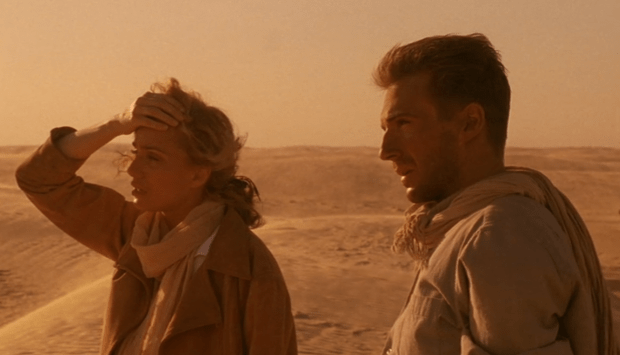

“If Wings has a claim to fame beyond the first Best Picture Oscar, it’s two million dollars worth of plane combat effects. They’re impressive (to a degree, don’t expect much) considering what they had to work with in 1927. The conventions of silent film mean that you’re going to watch a lot of flying time, so at least it’s well done.”

“Saying there are “problems” with Forrest Gump is putting it mildly, but they are all intentional problems. The camp factor of Gump is off every chart, even the chart they invented to show things that are off of charts.”

“I had to watch The Life of Emile Zola twice to really get it. It’s one of the shorter Oscar winners — almost none of them clock in at under two hours — but it’s still an unbelievable slog to watch in 2014. It’s a courtroom drama that mostly happens outside of the courtroom and it’s an exploration of race that never mentions race at all.”

“There are scenes that are a little obvious – a man in an extremely classy restaurant at one point starts a fight with Gregory Peck’s friend just because he’s Jewish – but for the most part, it’s a surprisingly reasonable critique of a difficult topic.”

“It’s not perfect, but judged among the other 1930s winners like You Can’t Take It With You, Cavalcade, and Cimarron, it starts to feel very special. It works in a modern setting, though it would need some tightening to work now.”

“The most important conflict of the film is that Salieri can’t handle Mozart at all. It’s a compelling conflict, but it centers on Salieri’s shortcomings compared to the great composer. Maybe this is crass, but it’s definitely a bit difficult to feel for a guy whose main failing is that he kinda sucks compared to Mozart.”

“Out of Africa has been rethought mostly because a 161-minute movie with (and this is a stretch) 2.5 characters is tough to pull off. Redford’s acting seems like it comes from many decades earlier, and it’s really hard to see how he got so much praise in the 80s for this one.”

“The two great crimes of The English Patient are that it focuses on the wrong things and that it beat Fargo, a much better movie.”

“Even the director of the film went on the record to say he was unhappy with Heston’s performance. The film was the most expensive film ever made, so you have to wonder if at some point they didn’t just decide to make an epic around him and hope it worked.”

“The dialogue in Titanic is awful. At one point Billy Zane’s character is asked about Picasso and he says “He’ll never amount to a thing, trust me.” Little garbage jokes like that are scattered through this thing, and I just can’t stand them.”

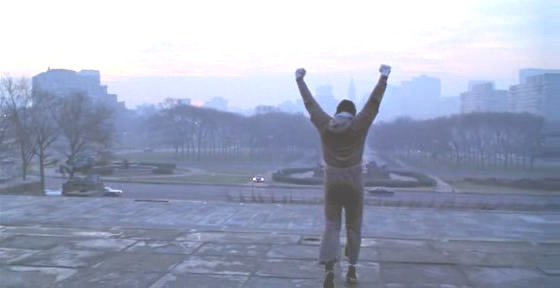

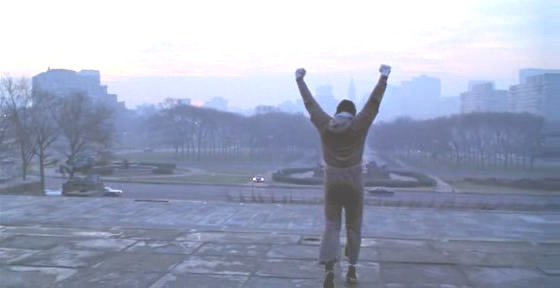

“It’s not the chilling tale of Taxi Driver and it’s not the risky parable of Network, but it’s fine. Rocky shouldn’t be what we have as the history of 1976, but it’s no huge insult to its betters, either.”

“There’s no place in modernity for a two-hour explanation of why you don’t have to put on the red light, and if there is, there isn’t a place for it to pretend that it’s one of history’s great romances.”

“Chicago is also supposed to be fun, and I was definitely surprised to find that I really enjoyed it. The songs are catchy and the dancing is flashy and it has Taye Diggs. Are you going to tell me you hate Taye Diggs?”

“It won’t be something I revisit very often, but I found myself caught up in an update of a story that I already know. That’s an accomplishment, so my bold take on West Side Story is that it’s “an accomplishment.” Really going out on a limb here.”

“Clara is nothing; she almost never even speaks. She’s upsetting in a 2014 sense because she struggles in a world that can’t accept her, but she’s ridiculous even in a 1955 sense because she just seems so damn bored in her world.”

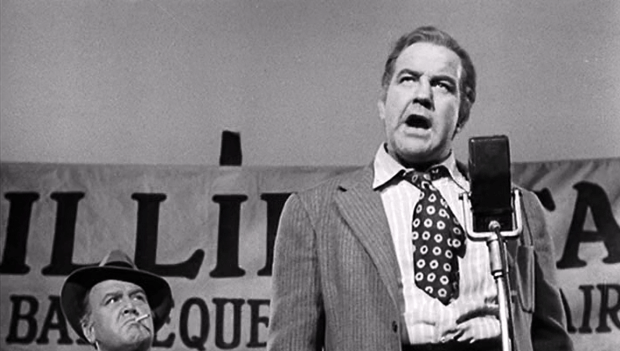

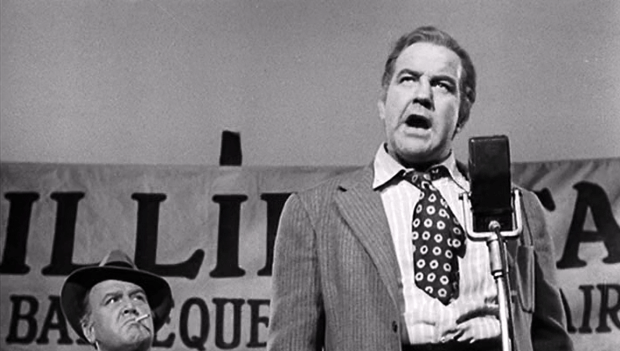

“There are weird choices that keep All the King’s Men from being one of the all-time greats on the list, but Broderick Crawford and Mercedes McCambridge turn in two performances for the ages.”

“Honestly, if anything is remarkable about Argo it’s that it’s awfully funny for a drama. Alan Arkin and John Goodman do a lot of heavy lifting in that department, and a bit role for Richard Kind never hurts.”

“A lot of the “John Nash is a genius” scenes are really damn pretentious. Towards the end he goes back to Princeton to haunt the library and be around smart people, and a scene between him and a young student drives right up to the cliff before stopping. It’s not quite terrible, but man, it’s rough.”

“There’s something we buy as an audience about two people who met when they were insanely young and then lost touch being in love, but think about that person in your life. Think about “risking it all” for that girl or boy from the first decade of your life. People may be mad at the conceit of a game show where a boy knows all the answers — and only these answers — but I just wish there would be a love story where the people had time to actually fall in love.”

“Berenger’s character is a brutal villain. War movies often only show one side of a conflict, so it can be tough to discern a “villain” in the classic sense. In this movie, it’s definitely him. He tries to sow dissent through violence and threats. He reacts to someone saying that he should cool down by burning down a town. He’s the violence in all of us wrapped up into one scarred up guy”

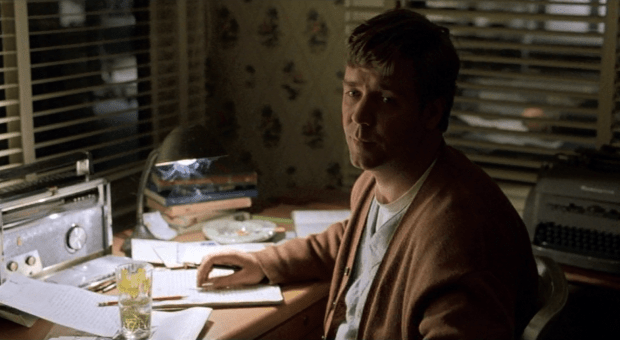

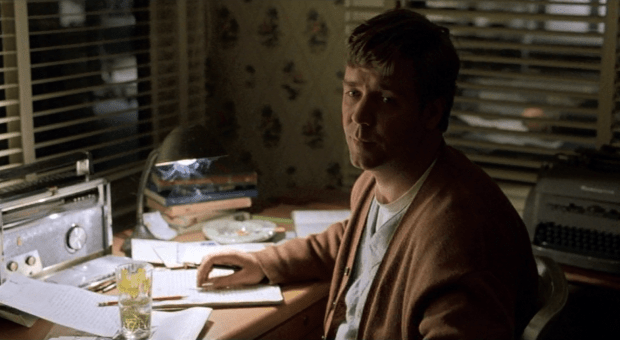

“That’s the main takeaway from The Lost Weekend: the shock. It’s a movie from nearly 70 years ago, but it’s about a universal reality of humanity. We like alcohol, but a lot of us are afraid of it. I don’t think anyone could watch this and not relate to Don, or at the very least the terror of being consumed by something completely.”

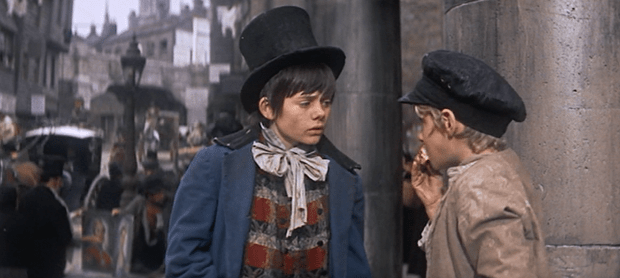

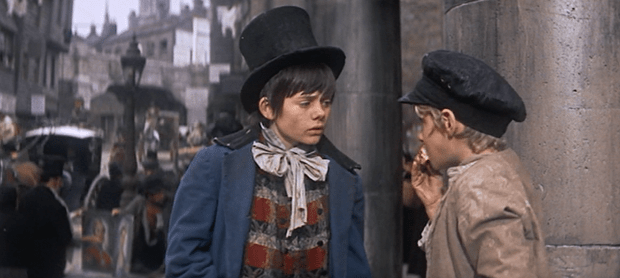

“The poverty of Oliver! is meant to be the star, really, and it is. No matter how much you steal, you have to steal more, and the thefts themselves erode your character in a way you can’t return from. Nancy is Bill’s girl (see: “As Long as He Needs Me,” the saddest “love” song) and Fagin is a career criminal (“Reviewing the Situation,” which is genuinely funny rather than musical-funny) and neither of them have any place to go, even if Bill would let them leave. The cycle contributes to the cycle.”

“The Departed is the story of two moles: One is a real cop embedded into a fake life of crime and the other is a fake cop raised to infiltrate the police to protect organized crime. It provides the necessary interesting twists and it plays with the idea of loyalty and reality.”

“Firth said after filming the movie that it was somewhat of a challenge to fully return to normal speech after affecting the stutter for the role. It’s a remarkable performance, to be sure, and it really sells the “journey” of the character.”

“Your typical sports movie is the story of an underdog either defeating a superior enemy or competing valiantly and losing. Chariots of Fire doesn’t exactly follow the template, but it’s assuredly still a sports movie that is about a bigger struggle.”

“There’s a lot going on among the sad cast of American Beauty, and even for all the obviousness of the main traits of everyone involved, the gchat-status tagline of “look closer” actually works. I don’t buy the teenagers’ interactions with each other anymore, but the response of “don’t give up on me, dad” as a way to cut through Chris Cooper’s brutal discipline of his son really, really works. It’s not that he’s responding honestly, it’s that he’s figured out what his father wants to hear. Who ain’t been there?”

“You know Julie Andrews. If I start one of these songs around you, you will be compelled to finish it. You can’t going to leave “Doe, a deer, a female deer…” hanging out there. You’re going to have to sing about a drop of golden sun, no matter how much of a heartless bastard you are.”

“Cruise is an interesting choice for a villain here and honestly, a mostly-evil protagonist is an interesting choice overall. It works because there are so many sad pieces to connect in Rain Man. “Meet your brother and try to earn back the three million bucks from Dad’s will” is a pretty fantastical plot, but “learn to live with your family and your place in it” is something much simpler to understand and believe.”

“There are modern complaints to lob at the 1960 winner for Best Picture, but it’s a phenomenal movie. Jack Lemmon gives what I’d normally call a once-in-a-lifetime performance, but most people don’t get to have Jack Lemmon’s lifetime.”

“Jeremy Renner is incredible in this. The entire movie is a series of brief, loud moments surrounded by long periods of quiet, but a particular scene where Renner and another soldier have to stake out a position with a long rifle with a scope is particularly tense. The exciting bits are exciting, but they work because they are buffered by enough time to let it all build back up.”

“History has both been extremely kind and extremely unkind to Gone with the Wind. It’s one of the most successful, well-reviewed films in American history, but it’s a film with a Wikipedia “analysis” section that includes “racial criticism” and “depiction of marital rape.” No matter what part of Gone with the Wind you’re talking about, you’re talking about something capital-I Important.”

“If anyone ever asks you if you’ve seen The French Connection, all you have to do is say “oh, man, that car chase is awesome!” That’s it. Maybe mumble something about Gene Hackman. Then change the subject and ask whoever you’re talking to about a neat fish you saw once. You made it out of that conversation, and I’m proud of you.”

“It would be enough if the movie were about the struggles to replace a ghost, but it wouldn’t be Hitchcock. The first act of Rebecca touches on that topic, though, and it’s fascinating to watch the young woman walk around an enormous mansion and try to figure out how to be someone she’s never met.”

“It’s just not possible to talk about the movie without getting into the best part, which is the big reveal of a second act. I’m not going to actually say how it ends, but it’s important to know that this movie isn’t what it appears to be, and if you don’t know what it is, for real, go watch it first.”

“The film is gorgeous. It is difficult to pick one shot to express that, but the racetrack that they visit to test out Eliza’s new vocal talents is a good candidate. It’s entirely colored in black and white and touches of gray, except for Higgins himself. He wants to stand out to frustrate the crowd, and he does so in a brown suit. The idea that a brown suit, the simplest of the simple, makes people aghast is ridiculous, and that really sells just how little difference there is between everyone.”

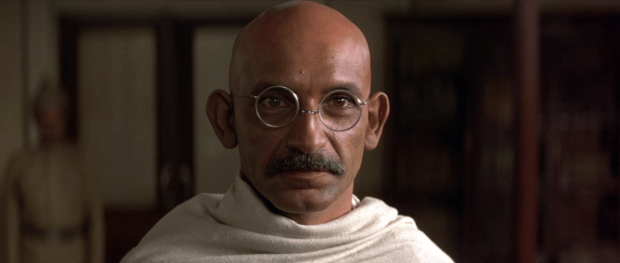

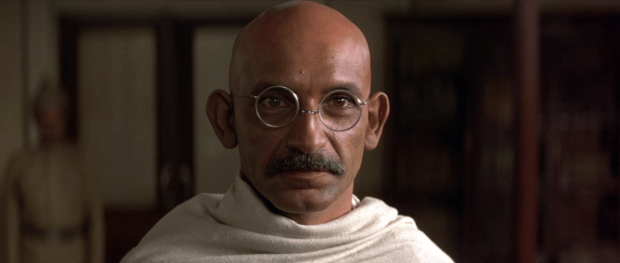

“It’s really a great choice to portray the man most consistently identified with “resistance” as being difficult to deal with. He’s a gifted leader and a man on a mission, but he’s also tough as hell to deal with.”

“O’Toole’s descent into madness is exceptional, especially the final 20 minutes before the end of part one. There are some tight closeups on him where his entire personality drifts and it’s just the face of a man capable of anything, for any reason.”

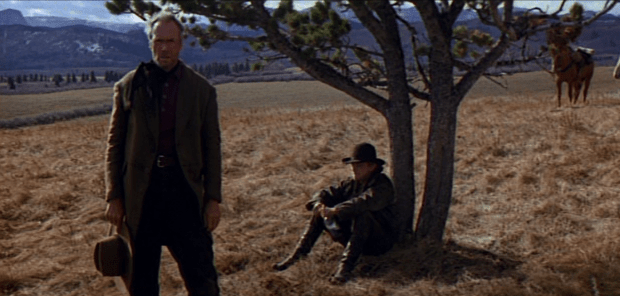

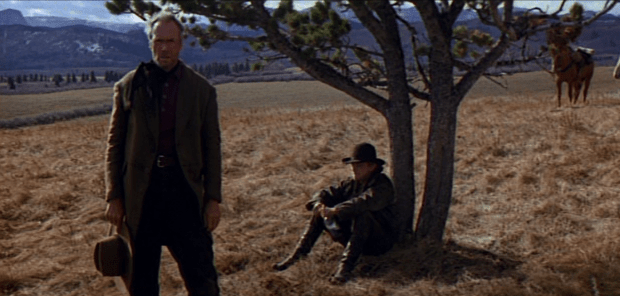

“Clint Eastwood can at best be called a “complicated” figure in today’s world, but his performance in Unforgiven is both terrifying and riveting, and he makes the entire thing work. Now he just needs to stop saying crazy shit to empty chairs.”

“The fight at Minas Tirith feels huge and important, and the shifting perspective from inside and outside the castle walls makes it feel more like a fully realized fight. There are multiple “starts” to the fight that all allow for different discussions of heroics and bravery. There’s nothing to not like about how the whole thing is handled, and the most fascinating part of it is just how early it happens in the movie. There’s an entire hour of “climax” after Minas Tirith, but it’s in that battle that the movie won its Oscar. Watch something like Troy try to do the same thing and you will gain more respect for it.”

“The sadness of the lead characters is extremely hard to handle. In one scene during the “hopeful” part of the movie, Jon Voight’s character has to ask a woman for crackers that he can put ketchup on to not starve to death. It takes a dip towards the depressing after that, but it’s still on the upswing, then! I list this in the “best” because the movie isn’t a direct arc, which is interesting. It’s a risky way to tell a story, but it’s like an actual life with highs and lows rather than one constant line up or down.”

“His tale is gruesome, but the tale of Patsey (Lupita Nyong’o) is even more unimaginable. To tell more is to rob her Oscar-winning debut performance, so let it just be said that her life is harder than the character described in the title of a movie called 12 Years a Slave.”

“It’s a look at how difficult it is to stand up for what is right and how sometimes, it doesn’t really make sense to do that right away. It’s a complex look at what initially seems to be a simple situation, and while it’s remembered in history for Brando’s amazing line read in one scene, it’s so much grittier and tougher than that 30 seconds alone.”

“Every war movie has to decide what it wants to say, but I can’t think of any other one that is as determined as this one to say exactly one thing. Surely Full Metal Jacket doesn’t paint a positive view of war, but All Quiet on the Western Front is relentless.”

“The performances are so tight that it’s easy to forget that the time and the setting mean that you already know everyone here is doomed. Whether you can look past that or not will determine how much you enjoy the film’s narrative, but you can’t ignore the greatness.”

“You should see it to focus on the struggles involved and the timelessness of this cycle: America goes to war, America sends Americans, Americans come home from war, America doesn’t know what to do with the war or the Americans. We’re a country obsessed with the idea of war, but we’re not always one that knows what to do with everything that goes into that.”

“Some classics are “important” and some are good. I can’t speak to how crucial It Happened One Night is to the rom-com as a genre, but it’s a movie from eight decades ago that wouldn’t need much updating to be released this summer. It’s worth your time, even if you aren’t watching all 86 of these.”

“Every time I expected a heavy handed treatment of race in a situation I was surprised. Right down to the eventual physical fight where Poitier has to literally run away from racists, it’s difficult, but it’s all the better for it.”

“There’s a very Catch-22 element to this thought process that’s both darkly funny and very sad. The tone’s lighter than you might expect at times for a movie about dying in prison camp, but as the movie stops being about one thing and becomes the story of how a project galvanizes people it really walks a fine line without seeming too absurd.”

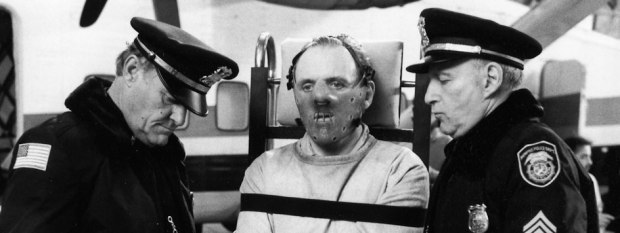

“You need to see Jodie Foster and Anthony Hopkins in this movie if for no other reason than to gain new appreciation for what you think you already know. You need to replace your acting benchmarks for greatness.”

“It’s depressing, intense, and dramatic. It’s probably too much of all three of those things, though that will depend on what you want out of The Deer Hunter. Even if you think the whole thing is too much — and some of the symbolism can’t be said to be anything but “too much” — you will get something out of it.”

“No Country is less about trying to hit you with a sledgehammer over and over and more about making you wonder if anyone in the movie ever had any other choice. It’s tough to spoil and I’ll try my best not to, but No Country sees a lot of bad things happen to some good people.”

“McMurphy vs. Ratched is one of the all-time great psychological battles in film, and the best part is that they’re essentially working the same angles. Both of them have each other figured out, and they go to work on the other patients with the same tools of manipulation. It’s when Ratched really amps up that the movie starts to hum.”

“It’s a heroic story and it’s told in thrilling fashion. The Nazis feel both like people and like monsters, which is a nice touch to keep some humanity about the entire experience. One of the important lessons in an atrocity is to remember that many of the “enemy” forces aren’t deranged or psychopathic, they’re standard, normal people. That’s what makes evil so insidious, and it’s an important component here. Most of the Nazis in the film aren’t cartoonish, snarling, monsters, and just as in life it’s too complicated to just pick out maniacs. You need to fear the good man who will do nothing, one of the great lessons of the Holocaust.”

“Is it better to be strong or to appear strong? At certain points of The Godfather, they’re both valuable. One of the many messages of the movie, though, is that you have to know which is more valuable in the moment.”

“The story is unassailable: it’s been done over and over since then, and you stand a good chance in this era to have seen a parody of it before the original. It earned a The Simpsons episode. That’s how we measure how lasting something is, right?”

“Patton, if nothing else, is the triumph of George C. Scott. He’s exceptional in Dr. Strangelove, but he’s all-time great, here. It would not be unreasonable to say that this is possibly the greatest single performance on the list, and this is one hell of a list.”

“Shirley MacLaine beat out her fictional daughter Debra Winger for the Best Actress Oscar, but hot damn Debra Winger is perfect in this movie. Emma leaps into her mother’s arms after coming home for a weekend and she moves with a fluidity and liveliness that perfectly sells her character. When she’s playing a 20-something trying to act like a real adult, the movement tells it all.”

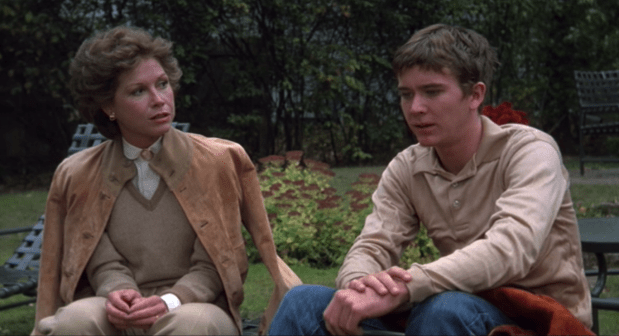

“What stands out the most is the difficult line that the story walks about who the “hero” is. We spend a full hour with Ted, but Joanna tells the court the story of the Ted we never got to see: married Ted. The real answer isn’t that Ted is a good father or that Joanna is a bad wife or that Ted is a bad husband or that Joanna is a good mother, it’s much more complicated than that.”

“Pacino’s Michael Corleone, who is just trudging towards whatever is happening next. He’s the engine that drives everything, but The Godfather Part II is just as much about what the powerful can’t make happen as it is about what they can. The sadness engulfs him and he walks around both about to explode in anger and about to dissolve in resignation, and the result would be enough to carry a much, much lesser movie.”

“It’s not hilarious in that “oh, I get it” way, either. It’s a legitimate string of jokes, big performances, and absurd doubling of situations that is still funny four decades later.”

“The love feels like love actually feels: complicated, painful, and overwhelming. Casablanca is a romantic movie and a war movie and it’s never one at the detriment of the other. It defies you to pick one of those to describe it.”

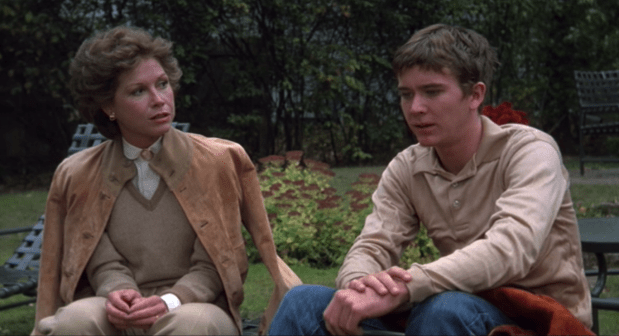

“Is Beth a villain, or is her response just one of the possible responses to grief? Is Calvin purely good, or do his choices with Beth show that he took a simple path through loss rather than ask some hard questions early? Does Conrad do the right thing, or does he just appear to do the right thing? There isn’t one correct viewing of Ordinary People, and though you’re likely to just say that Beth is terrible and be done with it, it’s definitely more complicated than that when you extrapolate this to your own life.”

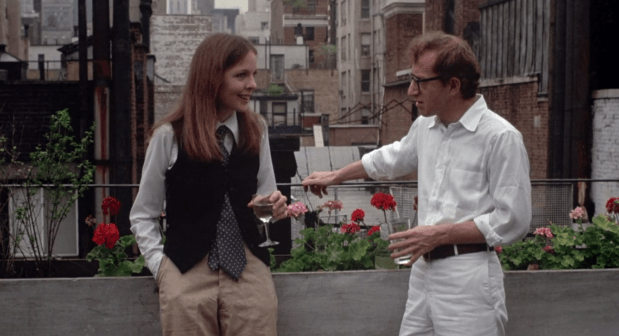

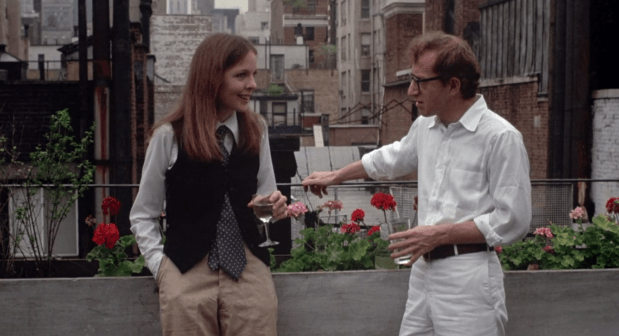

“It’s iconic because of things like Keaton’s look and Allen’s writing style, and those two things still shine through as superb. Watching Diane Keaton “la-di-da” on a New York street is always going to be a wonderful moment, even if Woody Allen’s legacy is more in question now than ever before.”

Alex Russell lives in Chicago and is set in his ways. Disagree with him about anything at readingatrecess@gmail.com or on Twitter at @alexbad. Image credits are available on the original posts. All uncredited images are screenshots I took myself, which is why they look worse.